Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Anderson Island Park & Recreation District, by virtue of its stewardship of various island parks, has the opportunity to facilitate projects that further our understanding of our rich island history.

Jacob’s Point Park is great example of a property where we have been able to feature island history for visitors hiking the trails – from the old Jacobs’ homestead to the recently opened access to part of the 1890’s brickyard.

As much as we know about the history of this part of the island and its previous residents, there is so much history left to discover:

The Park Board found itself thinking what a cool project this could be. Was there a way to offer our treasure-trove of potential history as an educational opportunity?

John Larsen contacted the Archeology department at Evergreen State College, and on August 31, 2020, Evergreen archaeologist Dr. Ulrike Krotscheck and ecologist Dr. Carri LeRoy met with the park commissioners to discuss the project.

They toured the trails of Jacob’s Point park to gain an initial understanding of the ecological habitats and archaeological profile of the park, and to determine a future scope of work.

They tentatively plan to bring undergraduate students from Evergreen to survey and investigate the park as part of a fieldwork class, possibly as early as the spring of 2021.

As the project progresses and becomes more well-defined, we’ll update the community, and share the journey of how your parks are revealing their history!

Evergreen State College archaeologist Dr. Ulrike Krotscheck, ecologist Dr. Carri LeRoy, and Park commissioner Chuck Hinds examine a map of the Jacobs Point property on Anderson Island. - August 31, 2020

As reported by Bessie Cammon in Island Memoir, George M. Brand of Elmira, New York, came west in 1889 to look for business opportunities. On December 3, 1889, Brand purchased property for a brickyard on what is now known as Jacobs Point from John and Celia Larson of Steilacoom for $2000. This was a time of booming economy in Pierce County. The Larsons had paid only $375 for the property in November, 1887. It is not known if they had cleared it or made any improvements, but soon thereafter, Brand put together a team of workers under manager Charles Anderson and brick making began on Anderson Island. Several of the crew had previously worked at the brickyard on neighboring McNeil Island, and so knew a thing or two about the process.

In the aftermath of the disastrous Seattle fire of 1889, brick had become the construction material of choice. Several Washington towns passed ordinances requiring all civic and commercial buildings to be built of brick or stone. This naturally resulted in brickyards springing up all over the region. Many of them were located on the water, as it was actually easier to ship bricks by barge than over the primitive roads of those days. Competing brickyards were located at Ruston, Fox Island and McNeil Island. Access to good clay was another factor in site selection.

The business was incorporated at Olympia in April, 1894 as the “Anderson Island Brick Works,” with a capital of $35,000 shares, 350 shares at $100 each. The incorporators were George Brand, Charles H. Anderson, and S.C. Heilig. The purpose of the company was “to manufacture and deal in brick, tiles, building stones, etc.”

During its heyday, 1890-96, the Anderson Island Brick Works employed as many as 24 workers. Many of the men who came to work at the brickyard settled down on the island and raised families here. The clay was dug from a pit located a few hundred feet inland from the shoreline using scoops (large shovels shaped like a wheelbarrow pulled by horses) and the bricks were molded by hand in wooden molds. Island tradition has it that the clay was of inferior quality, leading to the eventual demise of the business, but it is more likely that the depression which followed a world-wide financial panic in 1893 eventually brought the demand for construction materials to a halt.

A sort of graving dock, about 40 by 50 feet, was dug on the northeast corner of Jacobs Point, (visible today but filled with soil and logs) where barges were floated in at high tide and rested on a wooden framework when the tide receded. the barge would then be loaded with bricks. Meanwhile, barnacles and seaweed would be scraped off the bottom of the barge, which eventually was floated out on a later high tide.

It may well be that the island clay was not the best, but there were other issues that resulted in many of the bricks being unsuitable for sale. The shoreline on the north side of Jacobs Point is armored with broken bricks, many of which show that rocks and sticks were embedded in the clay and may have contributed to the breakage. Also, there is evidence that the firing process was not well-controlled, which may be deduced from bricks found on site which had melted during manufacture.

Doubtless some of the products of the Anderson Island Brick Works found their way to homes on the island and ended up in chimneys, cisterns, and the like, but a brick works of the size of this one needed big customers with big projects. There is an oral tradition that facilities built at Western State Hospital in the 1890’s used Anderson Island bricks. The following article appeared in the Vancouver, BC, Daily World, on Thursday, September 8, 1892:

American tugs Ranier and Rapid Transit are in port, one with stone and the other with bricks for the Hotel Vancouver Extension. the bricks are being brought from Anderson Island and the stone from Chuckanut Quarry, Bellingham Bay.”

A survey of the brickyard clay pit, which is now a frog pond, should yield an estimate of the volume of bricks made at the works. Evidently, the enterprise folded in the late 1890’s, and the property was sold at a public tax auction on October 15, 1904.

A map produced by surveyor James Israel and dated July 1908 shows the location of the pit and appears to show that there were 4 buildings extant at that time. Two of them, near the mouth of a small cove on the northeast side of the brickyard site, evidently represent a house in which Claude and Maud Jacobs lived while waiting for their new house to be built on the other side of Jacobs Point in 1915, and perhaps a shed or other out-building. There is a spot near the north side of the point where there is a large deep hole, approximately 6 feet deep when it was explored in 1978. It was probably an outhouse or perhaps a dumping pit. A few odd pieces of broken crockery were found there at that time. Not far from that spot were found the ruins of a small building, perhaps a cook-house or bunk-house, with bricks from a chimney and an old iron hoop of the sort that was installed in fireplaces for hanging kettles over a fire.

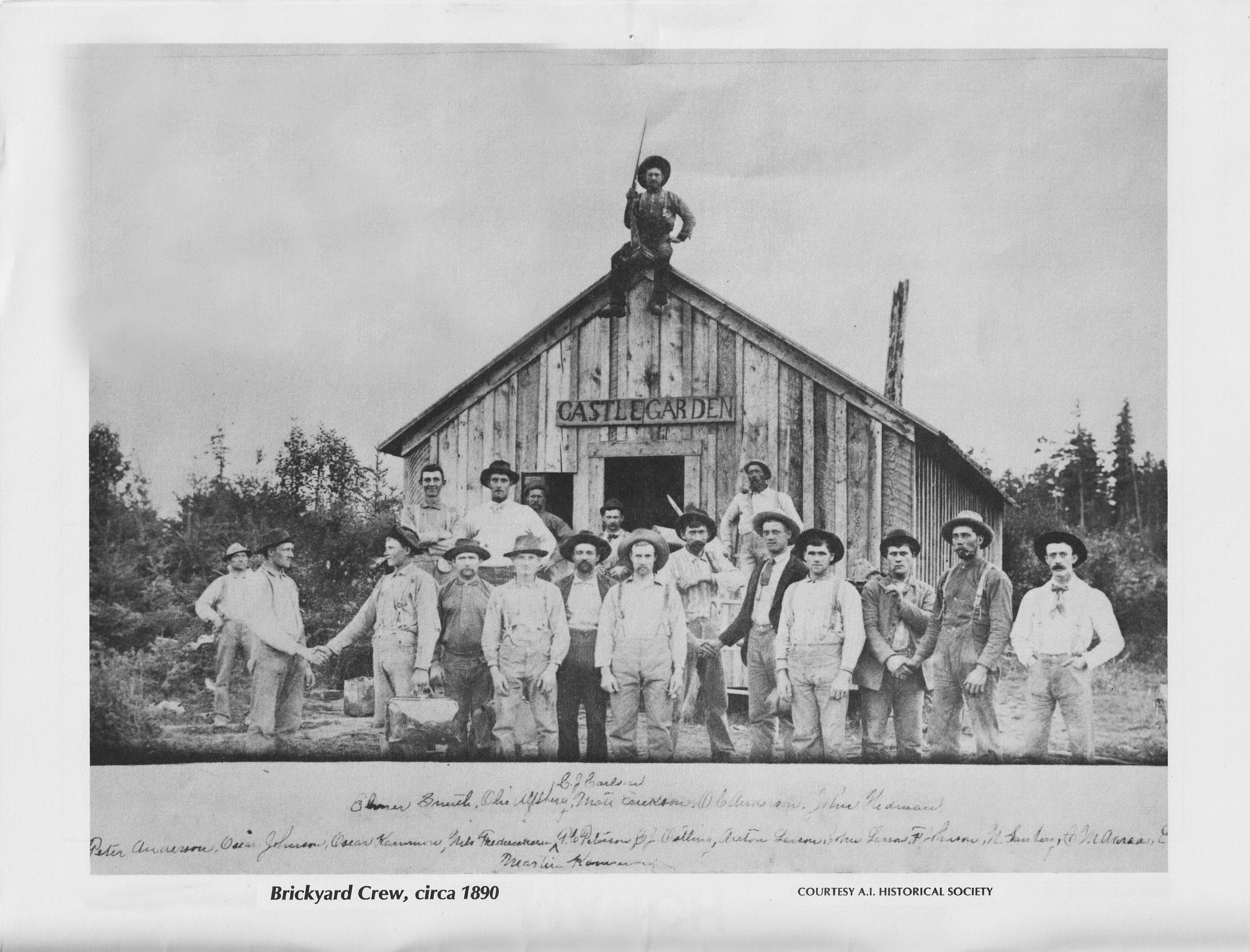

In Island Memoir, Bessie Cammon writes of a picture of the brickyard crew posing in front of the kiln, however no evidence of a kiln has yet been found on Jacobs Point. It is more likely that the photo shows the green bricks stacked under cover to air dry. The actual firing may have been done by piling the bricks up and building a fire around them. One thing is certain, the heat was provided by firewood – most likely Douglas Fir.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer of August 8, 1894, carried the following story:

“Eighty cords of wood belonging to the Brick Works on Anderson Island were burned last night, presumably by enemies of Charles Anderson, manager of the Works, who was recently shot in the face by the Carlsons, with whom he had trouble. He may move the Brick Works from the Island as a result of the alleged incendiarism.”

The following day, this article appeared:

“William Johnson, of Anderson Island, called today at the Tacoma Bureau of the Post-Intelligencer and stated that the origin of the fire which destroyed eighty cords of wood belonging to the Brick Works on the Island was the burning of slashings on premises adjoining. All the residents of the island, Mr. Johnson says, are law-abiding citizens and would not set the brick company’s wood on fire. While the residents were displeased with the management of the company, they would not commit any unlawful act.”

It may be speculated that 80 cords of wood would produce a spectacular blaze, such that even today, some 125 years later, there would be evidence of the conflagration in the soil at that location.

Recent site work at Jacobs Point has led to the discovery of a kind of patio, now buried under more than 100 years of duff, which is constructed of bricks laid on their sides on the ground. The extent of this “patio” has yet to be determined, but it appears that it might measure as much as 20 by 60 feet. Chances are that this may have been the floor of an open shed on which the bricks were stacked so as to air-dry before firing, which appears to be what is happening in the picture Bessie Cammon describes as the kiln (see below). Careful excavation of the rest of this patio may reveal the remains of a pole structure which might once have supported a roof. Air-drying was of the utmost importance if the bricks were to survive firing, and most certainly a roof would have been needed in a climate like Puget Sound’s.

Jacobs Point, situated between Oro Bay proper and East Oro Bay, became an island park in 2011. Sometimes known as Brickyard Point because of the factory which once flourished on the north side of the peninsula, most of the point was eventually purchased by B.F. Jacobs beginning with parcels belonging to W.R. Flaskett around 1910.

When young Claude Jacobs, a recent cum laude graduate in pre-law from the University of Washington, and his bride Maude, an elementary school teacher, wed in August 1915, they received a half-interest in the Anderson Island property as a wedding present.

It was Claude’s dream to try farming, and Maude, educated as a teacher, was “most willing to try to succeed as a farmer’s wife,” as she wrote later in life.

That winter, they lived on the family yacht, the Corsair II, while they renovated an old cabin on the site of the brickyard. Claude worked hard planting vetch for livestock feed and building pigpens and a new chicken house. The young couple quickly became friends with the Carl Ostling family, who lived on the farm across the bay now operated by the Martinez family. They rowed across the bay practically every day to get drinking and washing water.

Later on, B.F., Claude’s father, brought over two carpenters and work was begun on a new home on the other side of the point, facing what is known today as Brandt Road. Claude hand-dug a 40 ft. well. They put in a garden, sold eggs and cream, and made butter and soap. A daughter, Esther, was born in Puyallup on July 28, 1916.

Claude was also busy in the community. Being the only islander with a college degree, he was elected president of the Board of Pierce County School District No. 24, which operated the one-room school at Wide-Awake Hollow. He also served as President of the Anderson Island Social Club, the mission of which was to establish telephone service in the community.

The young family was beginning to develop roots on the island when World War I intervened. They abandoned their fine home in 1917 and from then on it was only occasionally a home to squatters and for a spell after World War II, to Claude Jacobs who had not given up his dream of farming. The house was still habitable as late as 1978, though the roof was beginning to fail. Today, all that remains is a tall chimney which once served a rather impressive fireplace.